One morning while cutting a roll of canvas she nearly stabbed herself in the stomach. But the tears wouldn’t come, the best she could do was a whimper that tasted of bile, so that after a few minutes she gave up. The city was quieter in the morning and all she could see was the wall outside with its stripped and flayed orange brick, standing like a blank lonely outpost. No one in the windows opposite who saw the slip and caught her eye, raising their eyebrows and mouthing a relieved cursory celebration. She knew, however, that the perpetually dusty steps on the street in front would be occupied, as they had been every day since she and Trevor had been living there, by the same people who sat fanning themselves over never-ending games of cards with crumpled packets of sherbet lemons acting as bets.

The heavy scissors had missed and left a small gash in the rug she was kneeling on, and a barely noticed streak on the wooden floor underneath.

Her room was dark, with only a sliver of the blue sky trailing cirrus light into it. Oona had no furniture, just a lumpy mattress under a bright navy throw painted over with planet-like flowers and a few large grey suitcases which she used as desks. The boundaries of the room were mapped in the curved surfaces of mellifluous glasses of water that she used for painting, and plastic grocery bags with upbeat cursive writing on them.

She sat looking with her mouth pursed at the line where the scissors had sliced the canvas. Slightly mutinous, because it seemed that her hands had failed her even though she had done this thousands of times before, and she could direct one to her closet, where several paintings stood leaning with their faces towards the wall in sullen proof. She then trimmed it carefully, and mounted it onto a wooden frame which had a powdery tinnitus smoothness which now gave way to the white of the canvas. It gleamed like a possessed thing. Her eyes began to water.

Every time she cut a new piece of canvas she worried that she had forgotten how to paint, had lost the ability to think of things apart and things to paint, her hands might freeze, something changing, her voice and tongue and eyes rolling up and the suppressed unctuous writhing fizzing thing would come pouring out from inside her and make her convulse. The most blissful thing to do now would be to draw the door, the window, the narrow closet, over and over and to mechanically replicate every detail exactly so that something dependable solid visible might emerge. Nothing new came to her.

She heard the crackle of the butter as it hit and laced the bottom of the pan in the kitchen and re-arranged herself, inexplicably conscious as if he could see her through the door. Trevor was awake. He hiccupped and she tasted the vinegar at the back of her throat, instantly regretting it when she felt her lip curl behind the closed door. Fried eggs, and then bacon, two eggs for him, she counted unconsciously, two for her, no bacon for her and a rasher for him. These sounds had animated their mornings every day for the past twenty six years. There would be dried egg white crusted on the stove. She put the lids back onto the jars of paints. They left rings of yellow and red on the floor.

Sometimes she felt it, a warm rush of attention down the spine. It is enough to be winged for a moment. And then her world would dwindle to the room and the flat and to Trevor, who knew her name.

The water ran very slowly in their bathroom, her hands lying over the fine down on her thighs which smelled always of Trevor’s ablutions, because the only time she thought of the softness of the down was when she was here, surrounded by his smell which was so much more comforting; the possibility of him against the man himself. Often she would think about their life together, and usually she would land on a hazy variation of their marriage being a decades long spasm of their eventual separation, that was the end that she was convinced of and so along with the real Trevor she had willed phantom Trevors into existence. She could never decide precisely why, she supposed it was natural to dream, and in optimistic moments she decided that it was to hope, but in more truthful moments – when she was away from him – she knew that it was for convenience. Which is why she placidly put on her dress for work every day, buttoning it all the way to the top, and stood in front of the mirror. Soft, curved haze, not quite lines or edges, her body seemed to her to fade into the surroundings. She felt drab and shabby.

Outside the kitchen was one long lip of smoke. She could taste the fat on the air. Trevor glanced up and back.

‘Yours is on the table.’

‘Oh, it looks great, thanks, Trevor!’

‘Mmm. I use the right sort of pepper,’ he said. Slightly nastily, she thought.

‘I didn’t even know there were different kinds. You’re so good with these things.’ A high, fluttery laugh.

‘Oh, don’t leave the washing up until you’re back from work, I hate when the sink fills up.’

‘I’ll be back a bit later tonight.’

‘Sorry for interfering with your social life.’

‘Did you talk to your friend?’

‘About what?’

‘About the house we looked at.’

‘I’d have told you if something came up. Dave’s busy.’

‘Too busy to talk? You know, it’s fine if you don’t want to leave.’

‘You always leave the sponge soaking, it smells.’

‘You can wring it out yourself; we don’t want stagnation in the flat, do we.’

‘Everyone can’t be as passionate and free spirited as you, can they?’

The eggs beamed a ghoulish grin of yellow on greasy white.

This exchange wasn’t unusual, and they ate in silence. She was quiet and still, deliberately not letting any hint of anticipation slip, and the restraint was something physical and sweetly painful. She was going to a performance tonight, an actor was going to read from an unpublished play, and she had been planning for it for months. She and Trevor had gone to watch one of his films after an argument over his misplaced notepad and she had walked away from it in a daze, her hand held limply in his.

‘I know I forgot where I put it but you shouldn’t have thrown it on the sofa like that, you know.’

‘What?’ She felt winded.

‘The notebook. You can be so dismissive, so you found it, that doesn’t mean you should throw things around. It’s unpleasant.’

‘Oh. Yes. I didn’t mean to.’

‘I know. It’s all right.’

Trevor smiled at her, condescending, guarded, expectant. He was so sure. Sometimes she would try to feel him under that certainty and at those times she realised that she didn’t know him at all although she would tell herself that she did. After all this time. Was it her, was she naturally ‘womanly’ and unstable enough to make him climb under that shell?

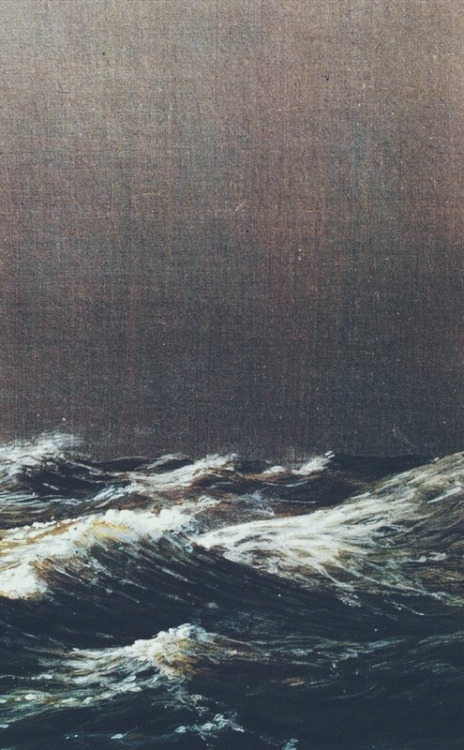

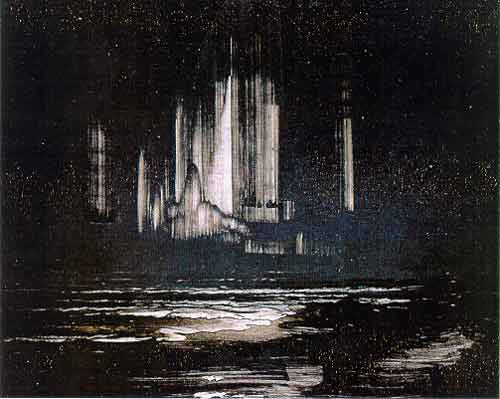

She walked down the steps to the street, past the card-players, and the fronts of buildings balanced upon a hinge opposite each other seemed to close on her, and she often hoped that what they hid from her was like the honeycombed inside of a pomelo amidst lichen stained walls cascading down over New York; skyscrapers rising with light at their centres in a relentless movement like a carpet of hundreds of spherical crystals moving as one, bubbles floating up in glasses of water, people with their voices weaving reverberations, and a salty sinewy foam net of windows with rows of plants spilling onto the sills, dogs on leashes on the streets beneath, and buskers over whom sonorous planes sped past anonymously.

The glimmering weight of the leaves shifting like water beyond the granite straight arris of the building which she would have to touch to make real to feel the grain and how different it is from the grain on her canvas, the fact of the touch is like a sensation of passing and in her head it is a stroke on the white. Rows of windows and doors curved away in front of her in a purple black series of serrations. The sound of leaves fluttering, chirping like insects with the ridged edges running across each other like teeth, car tyres held frenzied in place, cupping the indeterminate electric hum characteristic of a large city.

A group of nuns glided past, somewhat shocking in their presence outside in the sunshine on a busy street. They excited her, the pious sartorial choices under which she imagined herself, wearing a bold yellow dress. A wasp. Trevor made appearing pretty into a fraught terrain, she didn’t know when it had happened but she realised one day that he resented her making herself up to go out. It amused her at first, then irritated her and finally drove her to subterfuge.

Abi was standing outside the store, smoking a cigarette, as Oona walked over. The name of the chemist was displayed in soothing menthol green above the silver bordered front.

‘My dog isn’t feeling very good.’

‘What’s wrong with him? Is it still his ear?’

Abi dropped her cigarette and kicked it around on the pavement.

‘No. I don’t know.’

‘Oh dear. That’s not easy.’

Abi glanced up at her and Oona found herself fiddling with the hangnail on her left forefinger. How sympathetic was she expected to be? Then Abi smiled and took her arm and they walked into the store together in their matching dull green uniforms. This was unexpectedly warm.

There were two other people who worked in the store with her, a girl at university working part time – Dee, who set alarms and timers for things without actually paying attention to them, talking on phone, moving when alone, a pimply cleaner, and Abi the supervisor.

She went into the awkward curve of the till counter and pinned a nametag to the front of her dress. The other girl who worked at the store was already at her counter, right in front of Oona. Dee’s fingers played impatiently on the lined metal edge as she turned the display on. Her phone vibrated. ‘Yes, I know,’ she mumbled to it. She often carried a half conscious dialogue with the seemingly spontaneous outbursts of her phone.

‘How are you, Dee?’

‘Snowed under, I’ve taken on another part-time job and I barely have time to go to class. How was your weekend?’

‘Well-‘

‘Hang on, it’s only about two minutes to opening time so I’ll set an alarm.’

‘Oh, what a good idea.’

She tapped away at her phone and then put it to one side with an expectant smile at Oona.

‘One of my friends put up their stuff for an exhibition on Friday and Saturday and I thought of you. Are you working on anything new?’

‘That sounds very nice. Where was it?’

Dee waved a hand and rolled her eyes. ‘Nowhere real. It was just him being vain. But tell me what you’re working on.’

Oona shifted. ‘Nothing at the moment, I haven’t felt like painting.’

The alarm on Dee’s phone went off and she turned it off impatiently.

‘Why not?’

‘I don’t know, people just don’t seem to like my work very much.’

‘Who’ve you shown them to?’

‘Just a few friends.’ Her old geography teacher.

Dee looked at her, mouth slowly curving into a smile.

‘I know just what you mean. I want to be discovered, too.’ She was leaning forward, hoops swinging, eyes wide and shining and her clear voice which sounded like it had never been ignored.

Oona’s forehead creased.

‘I didn’t mean it like that. But you’re probably right.’

‘I know I am. You know, you should let me buy you make-up, my sister bought it for me and now I don’t even like going out of the house without it. You’ll see, it’s such a boost to your confidence.’

She smiled at her and turned away. Oona ran a finger over the knob of bone on her wrist repeatedly as a woman with her two children came up to the counter. She put two large bottles of cough syrup down and began fidgeting with her purse while trying to hold both her children’s hands at once.

And it was over. Oona drummed a tattoo with her fingers as Abi came over to lock the till and Dee stepped away quietly, different and dimmed now.

She took her bag out from under the counter as Abi ushered her out of the way. The bathroom was at the very back of the store behind a door with an unreliable handle. She took off her dress and pulled on a thick blue jumper with a high collar and a pair of black slacks. They were slightly more transparent than she had imagined, and the pale skin showed up in a smoky grain. The jumper came down to just above her knee. She felt ridiculous suddenly, inadequately dressed, far too youthful. She took out a roll of lipstick from her purse and applied it carefully. The door swung open as Abi came in.

‘Look at you, you look like a little girl!’ She laughed and then caught herself. ‘You look lovely, where are you going?’

‘Just dinner.’

‘Ah. Tell Trevor I said hi.’

‘I will, Abi. And don’t worry too much.’

Abi touched her shoulder and then went into the stall.

The sky outside was rushed and tumbled and wide, wisps of clouds indenting it like the smooth bumps of citrus peel, the street could disappear, open itself and fold the other way like wings, and they could all be bewildered by a windswept desert with coiled rocks and grass rolling in its wisps. Sometimes she took different, smaller streets so that she could feel herself navigating the city and then arriving somewhere. She didn’t feel invisible, almost the opposite, she felt that her transience was normal here.

As she passed a trio of boys standing by a bus stop, one of them bending to flip his long hair over as the other two scrutinised it, she heard a sound. No, she wasn’t sure what she heard or even if she did hear anything at all, but she turned her head with a preternatural instinct and saw her. There was a gap between two buildings leading to an enclosed courtyard with a waxy concrete floor and high sides.

A woman was crossing the courtyard and there was something about her that unsettled Oona. She was very old, and folded upon herself, a scarf tied around her head in a large triangle and a misshapen woollen patched shawl spread over her shoulders, out of the folds of which she gripped a basket with a tiny dog in it. But what she was doing could not be called walking, the closest word Oona could think of to describe it was grating with all the noise and associations of the word setting off sibilant little sparks against the oily sheen of the ground and the soft trembling folds of flesh hanging from the woman’s face. There was nobody else in the courtyard except for her and the staring dog. It occurred to Oona then how human-like dogs were, and she wondered why she had never noticed this before. For the first time she hoped quite seriously that Abi’s dog was all right. This one especially, with its almond shaped eyes and a haughty delicate snout above a hairless mouth, took her back to the dead silences of her parents reading her annual report card from school. It was in the twist of the mouth. When she moved, Oona saw that there were flowers on her shawl.

It began to rain, very gently, streams like colourless hair. There were posters with faces of missing people held damp by tepid fluttering sounds of water, coils of silver foil, an old sodden notepad, and pieces of labels from jam jars lying in the cleft between the pavement and the road. The woman stopped and looked at her, and Oona remembered dimly an evening at the cinema with Trevor, when she had walked to their car as if in a dream. She stood there in the rain. Wearing her shawl made of prized rolls of patterned wool seldom used.

She arrived late at the theatre, the streets were slick with the reflection of the red and gold façade of the building. A few people in dark coats held newspapers over their heads and peered at the programme tacked to the wall. Her hand sketched the air at her side and she felt impatient now, for her empty canvas while walking slowly along the rows of chairs looking for an empty place. She thought of the rain and the courtyard and having to wait longer and longer for inspiration amidst all the grimacing and mincing, and then she scolded herself for being unfair as she found a place to sit.

When he walked onto the stage she saw that he had a transcendent, wonderful face. The smile of very young girls who ran around and stole biscuits during long silent hot crackling summer days; it was a sweet, acidic innocence, fleeting and poised. It was an actor’s smile convinced of the certainty of its world. The air around him thinned and disappeared as he took it all in from a roomful of silent people, who for several motionless moments subsisted not on oxygen air but on him alone, when the limpid cline of the eye seems to slip over the whole face, lips parted in soft wonder when note and light comes together and for a fraction of a second you recognise the moment as it is, in one stroke both as participant and onlooker. And it was like this that she witnessed him – transfixed, fragile, still; struck with the words that he was speaking and the breathing silence of their effect, his face rippling with a multitude of expressions like a mirror to her own. She thought of being in love with him, perhaps she was, had been dreamily for the past few months. She imagined choosing colours for him, the plane, the angle, the cadence, the pressure of the brush, everything, living in the upside down smile that they would share in bed. And then felt the lesser because she needed it so much.

Her hands played around the edges of her jumper. She ran her fingers over the intertwined wool, half listening, half looking. Every now and then he would look around at the audience, as if to find someone, or to collect the impressions that he saw, expressions of boredom or rapture or anywhere in between, or to will himself away. And she moved her head, she tilted it, she pulled the collar of her jumper up to her ears, hoping that this strange behaviour would make her exist for him and lodge this movement in his mind.

Trevor opened bottles which fizzed, popped bags of crisps, moved furniture around in the middle of the night and closed cabinets loudly. He walked with a strange bouncy gait which resounded throughout the flat like the galumphing of some horde. His coat lay over a chair in the living room, the only thing she could call hers was a large bag filled with and a pair of rotting apples. He played music while showering, always dimmed the lights when he left the room. A picture he had hung lovingly on the wall, a collection of fridge magnets arranged in some arcane pattern. She went into his room once when he wasn’t there, tentatively, lip bitten, and stood there and thought about how long it had been since she had seen him, she had forgotten what he looked like. She had never seen this man, not really. She imagined spending mornings together, not just scenic frozen contrivances but gazes, hurried touches, such a world of their own built itself as he spoke. She would have him read to her, this man with his sparkling voice. And there would, perhaps, be affection. He might glance at her while reading, this later more intimate glance an extension of a clear-eyed moment in a darkened room. Something had gone awry and she had woken up to find that she had not done enough, she was suddenly frightened of him, of the desperation that must go hand in hand with his ease, thinking of the hours that had gone into setting his face just right in the mirror, making sure his hands moved convincingly and that his voice flew tight and precise on a wire. It was like something pressing down on her, hands spread over her ribcage, something breaking with the shock of nothing. Language, the pulp, the bare structure, bones, blood, mucous, the sounds that appeared so refined now, suddenly noticed after a long day, imprecise comparatively, blunt and inelegant and visceral – and nothing, with no meaning anymore.

Then it ended and he left. The hall emptied out in disembodied bursts of laughter and the occasional raised voice. She sat in silence. Her hands ached when she thought of the walk back.